Woodrow Wilson’s Western Tour–and the “truth squad” that trolled him and the Senate Republican opposition in Washington–produced the greatest debate on politics since the Lincoln-Douglas debates.

A notoriously shy man who detested face-to-face negotiations with Washington insiders, Wilson made public speaking the centerpiece of his presidency. Wilson had a long history of “going over the top” to fight his political battles. As president of Princeton University, he spoke all over America during the controversies over eating clubs and the graduate school. As governor, he defied old-style Democratic bosses with his high-minded rhetoric. And so, naturally, he took to the rails when he faced the defining moment of his presidency.

Act I: Fractured Triumph

- Coming Home: When Woodrow Wilson returned to the U.S. from almost six months in France, where he negotiated the peace treaty ending the Great War, he awaited the biggest challenge of his career—convincing the U.S. Senate to embrace the League of Nations.

- Tommy and Woodrow: Who was the twenty-eighth president of the United States? Thomas Woodrow Wilson was an unusual blending of idealism and ambition, tempered by physical maladies that forced him to compensate. Those compensations have him unusual skills and tools—but also significant liabilities

- The War at Home: Home again, Woodrow Wilson faced a raft of domestic crises after six months in Europe—labor and racial unrest, race riots and a surge in lynchings, inflation and unemployment, domestic repression, the start of the red scare, the Spanish flu, and more.

- Into the Fire: President Wilson struggled to persuade Senate Republicans. Henry Cabot Lodge, an old foe, led the emboldened opposition to the League.

- The Decision to Go: With the public’s support for the treaty broad but lacking intensity, President Wilson decided to take a month-long, 10,000-mile “swing around the circle” to rally the American public behind the treaty, especially in western states where opposition might be turned in two or three states.

Act II: ‘Eye to Eye and Face to Face’

- Leaving Washington: Amid fanfare and last-minute conferral with allies, President Wilson left Washington.

- Talking Points: The tour was arranged hastily, without a coherent strategy for defining and arguing issues. Before leaving Washington, Wilson typed a list of talking points but prepared no texts for speeches. The talking points guided the president’s extemporaneous speeches but often caused him to veer off-message and undermined his argument.

- Opening Day: On the first day of his trip, Wilson faced a muted reception in Columbus, Ohio, where Republicans worked behind the scenes to undermine his visit. Wilson began as he said he would, with a simple “report” to the people without pitched rhetoric or partisan appeals. As he moved to Indianapolis, Wilson drew criticism for his explanation of Article XI of the League’s charter—and his call for Republicans to “put up or shut up.”

- A Shift in St. Louis: In Missouri, the president faced his strongest opposition—a rock-hard Republican Party that had resisted his administration’s policies on all fronts but the war itself, as well as a Democratic senator who embraced reform but abhorred the League of Nations. But he seemed to score with his pitche to the interests of businessmen.

- Kansas City: After a stop in Independence, Wilson spoke to a raucous crowd in Kansas City, where he used an anti-Bolshevik appeal to call for adoption of the League of Nations.

- Des Moines: In perhaps his best speech, Wilson laid out a comprehensive case for the League of Nations and received his warmest welcome to date. For the first time, Wilson and his aides believed they found a winning formula for the tour.

- ‘Hyphenated Americans’: In Nebraska and South Dakota, Wilson’s rhetoric sharpened as he attacked the Germans and questioned the patriotism of Americans who opposed the treaty. By rekindling the wartime enmities, Wilson undermined the very promise of the League of Nations.

- The Twin Cities: The president warned that chaos—in the U.S., and around the world—would result from rejection of the League of Nations.

- ‘Truth Squads’: As Wilson made his appeal, the Republicans sent a team of speakers to counter his arguments. Republicans against the treaty often attracted bigger crowds with their strident rhetoric against the president.

- Bismarck: In his strongest appeal against isolationism, Wilson warned that the U.S. could never again disengage from world leadership. Wilson broke from traditions against “entangling alliances,” the defining spirit of American foreign policy since George Washington’s farewell address.

- Pathos and Ethos: As his health faltered in Billings and Helena, Wilson made his most emotional appeal for the league, evoking the war dead and his promise that the Great War would “end all wars.”

- Why Coeur d’Alene? Wilson could never convince Idaho’s William Borah, the most “irreconcilable” senator, to vote for the treaty. So why stop there? The visit affords a glimpse into Wilson’s magical thinking and lack of discipline—and his belief that more words are always better than fewer words.

- To the Pacific: On the advice of aides, the president used simpler rhetoric in his appeals in Spokane and Tacoma.

- Gone was the confusion of earlier arguments—but also missing was the passion he needed to persuade a reluctant public.

- Radical Seattle: As he struggled with his health, the president reviewed the Pacific Fleet in the biggest welcome of the trip. But the trip was ultimately defined by the city’s ongoing labor tensions, which had produced a general strike in February. An unusual protest during Wilson’s parade devastated the president.

- Reckless Abandon: The tour’s overwhelming pressures found tragic expression when a car crash outside Portland killed two reporters covering the tour. The relentless demands of the tour would ultimately claim the president himself.

- Bullitt Explosion: Reports of opposition to the treaty in his own administration created a new crisis for the president.

- Senate testimony showed that Wilson’s own Secretary of State spoke cynically and dismissively of Wilson’s performance at the Paris Peace Conference. But when confronted by disloyalty, Wilson lacked the nerve to fire him.

- Bumpy Ride: The president’s health issues reached their peak as the train traveled into California.

- Into the Bay: In California—the home of Hiram Johnson, the treaty’s most unusual, active, and implacable foe—Wilson struggled to arouse popular support that would put Johnson on the defensive.

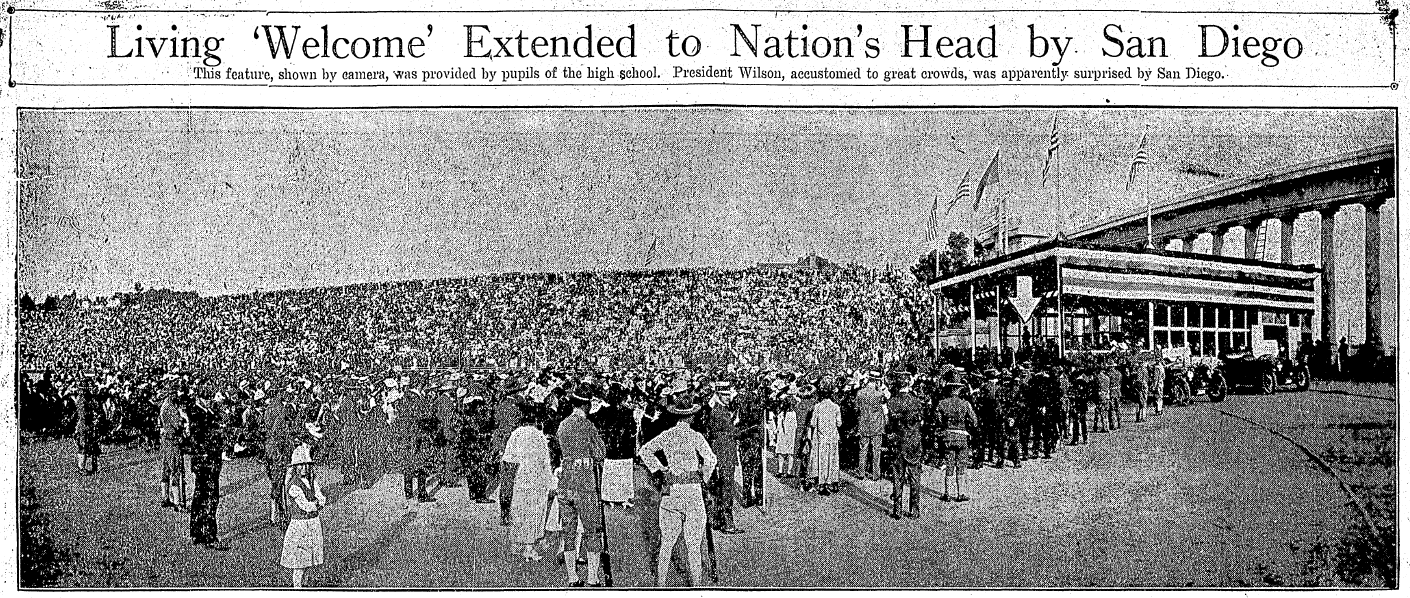

- A Bigger Voice in San Diego: Using the new “magnavox” loud speaker, Wilson spoke to more than 50,000 people in a San Diego stadium.

- As his health faltered, the press and San Diegans wondered how Wilson’s appeal might have been amplified by new technologies for connecting presidents and people.

- Reunion in L.A.: As the size and enthusiasm of crowds swelled, Wilson seemed to reach a peak. His rhetoric soared and reluctant followers and critics were becoming believers again.

- Reno: Wilson revealed future of presidential communication with an address sent by radio to other locations around town. Wilson’s style would have uniquely matched the powers of radio; he could have invented the fireside chat if he had the opportunity. Alas, Wilson lived in an era that lacked the technology to deliver words to the masses.

Act III: The End

- Latter-day Saint: As Wilson arrived in Utah, the Mormon Church was in the midst of a bitter civil war over the League of Nations. The president of the Church of Latter Day Saints supported Wilson, but the opposition remained intense—especially in the state’s congressional delegation. Those tension boiled over in Wilson’s address at the Mormon Tabernacle.

- Culture Clash in Cheyenne: Cowboys and Indians greeted the president as his tour began to wind down.

- Mile High: Split in its loyalties before the U.S. entered the Great War, Denver became a center of anti-red hysteria and violence against antiwar and antilabor sentiment. At a morning address, Wilson carried the audience with his patriotic appeal to lead the world.

- Closing Argument: In Pueblo, Colorado, Wilson found a city that reflected the diversity of the American West. Battling physical ailments, Wilson rose to deliver his most emotional appeal of the tour.

- Collapse: Wilson seemed to be revived by a long walk, where he met farmers and veterans of the war. En route to Kansas for the next stop, Wilson collapsed and the rest of the tour was cancelled.

- Impotent: Back in the White House, the president suffered a stroke that kept him out of the public eye for the rest of his presidency—never to speak another word in public. Twice, Wilson rejected revisions that would have led to Senate approval of the League of Nations. Now lacking the power to stir people with words; without his rhetorical skills, Wilson was a bitter and powerless figure, able only to react.