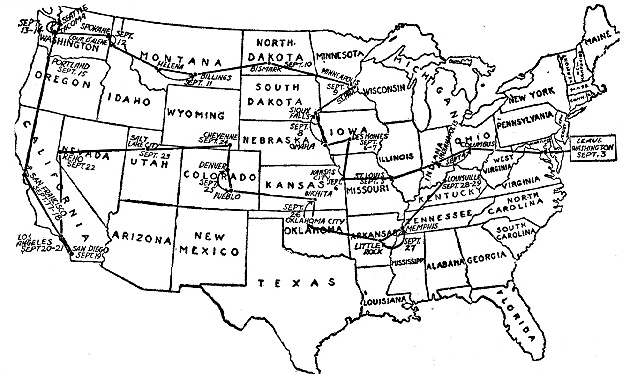

Frustrated with the treachery of Washington, Wilson hastily arranged a “swing around the circle,” a speaking tour of twenty states in September 1919. Traveling by train, he speak in state capitols, auditoriums, stadiums, fairgrounds, and railroad crossings. With all the logic and care of a college professor—and with the soaring rhetoric, threats and cajolery, and populist appeals of an opportunistic politician—he would explain why the League was essential to prevent future bloodbaths, avoid an expensive arms race, and protect American democracy from a permanent wartime footing that threatened basic freedoms.

The tour’s early going was rough and uncertain. In Columbus, Republican operatives worked to dampen turnout for his welcoming parade. But he found his footing in St. Louis and tested rhetorical themes as the tour moved into the upper Midwest and then the Pacific Northwest. He found warm greetings in most places, where sightings of presidents were rare. At a time before radio, the president was an exotic creature who aroused curiosity. Still, eager as they were to see and cheer a president, most Americans were weary of war, stagflation, labor strikes, a flu epidemic, and race riots. Most communities were eager to tend to restore some sense of normality.

Even when he met enthusiastic crowds, Wilson’s campaign did not convert any senators. In fact, some turned against the treaty after Wilson’s appearances in their states. Wilson’s only chance, then, was to create an overwhelming wave of public support that would crash against the Senate and wreck the Lodge coalition. To overcome his losing position, Wilson planned to end the tour with a grand final argument—with big, enthusiastic crowds in states with senators who opposed the League. This final argument, he believed, would prove irresistible.

On the road, Republican “truth squads” often followed Wilson with rallies of their own. They called Wilson everything from a native and soft appeaser to a traitorous villain. They claimed that Wilson was yielding American sovereignty to a foreign body that would be dominated by the very forces that created the world war in the first place. Sometimes they depicted Wilson as an egg-headed fool; other times they depicted him as a ruthless power monger. At many G.O.P. rallies, speakers whipped the audience into a fury. “Impeach him!” they called at a rally in Chicago.

As Wilson slogged forward from one city to another, he shifted his themes and struggled to focus. In his rhetoric, Wilson had always talked his way into arguments. Old students at Johns Hopkins University remember the time he described the inevitable expansion of democracy by concluding that a black woman would one day be elected president. That preposterous notion emerged from a long train of thoughts about expanding suffrage and opportunity—but in segregated Baltimore, it was a scandalous idea. But that’s how Wilson worked. He spoke and spoke and spoke and ended up who knew where—great for exploring history and the inner logic of reform, but dangerously unfocused for a president on a mission. As Wilson spoke, his detractors defined his cause more effectively than he could.

Still, as the president worked down the Pacific coast from Seattle and Portland to the San Francisco Bay Area and then down to Los Angeles and San Diego, the crowds grew bigger and more enthusiastic. Wilson finally found his pitch, a gaudy mixture of nationalism, ethnic populism, religious evangelism, and statesmanship. His words, the reporters on the train believed, were beginning to work. Crowds were enthusiastic; Wilson might just end the tour with enough momentum to force two-thirds of all senators to back the treaty on his terms.

He only had to keep up the pace in the final stops, in Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Arkansas, and Kentucky. Now that he found his groove—that was the biggest challenge—he now just had to keep it.

But weeks of hard labor, traveling in a steel train that trapped heat and swayed on the tracks, had worsened Wilson’s lifelong, debilitating ailments. He suffered splitting, blinding headaches and severe gastrointestinal illness. He could not eat more than a couple bites of food; sometimes he only drank cups of black coffee for meals. He could not sleep. His doctor propped him up in a train car, where he would get just a few hours of sleep before the train arrived at the tour’s next stop. At times, he could not control his thoughts. The words still flowed but they also veered off the subject. He contradicted himself, turned toward anger, struggled to explain his case. During one of his last speeches, at the Mormon Tabernacle, he almost collapsed. His suit soaked with sweat as he stumbled off the platform; when he changed into new clothes, they instantly soaked once again.

The punishing travel broke Wilson. His body shivered and convulsed; his headaches blackened his mind; his body grew thin and gray. He may have suffered a mild stroke on the tour. He was, as one visitor said, a “ghost.” Once the most active of presidents, he struggled to husband enough energy to climb the podium and speak for another forty minutes.

Finally, after an emotional appeal in Pueblo, Colorado, his body gave out. His doctor and wife implored him to halt the tour. He refused, fearful that quitting would ruin his cause and his reputation. Finally he agreed to cancel the last stops on the tour. The train returned to Washington. Days later, Wilson suffered a stroke that incapacitated him and even led to a brief effort to remove him as president.

For his last year and a half in office, this most voluble president never spoke in public again. Twice the Senate moved to pass the treaty with reservations, which would give Wilson a partial victory on the greatest initiative in his career. Both times he instructed Senate Democrats to vote against the treaty. He vowed to fight again for complete victory. He would make the treaty the centerpiece of the 1920 presidential election—he might even run himself for a third term—and the U.S. would join the rest of the world in a League of Nations that would eliminate 99 percent of all possible wars. But Republicans, running on a promise of a “return to normalcy” in American life—isolationism, lower taxes, less regulation, opposition to all meaningful reform—won a landslide election in 1920. Wilson died less than four years later.